Uncover Oporto's vibrant flavors and culinary gems with our expert guides. Plan an unforgettable trip now!

Read more

EXPLORE ALL OUR GUIDES TO PORTUGAL'S WINE REGIONS

Last updated: November 27, 2023

At first glance, little has changed in the magnificent Douro Valley. The river winds its twisty path towards central Spain as it did centuries before – over 900km of the majestic landscape remains totally unspoiled. Indeed, this is a wild and rugged vineyard, with hard, rocky slate and granite soils suitable for growing vines and olive trees but little else. Meanwhile, the descendants of the original Port families – Fronseca, Kopke, and Taylors – are still running the show. The often-predicted corporate takeover has yet to arrive. Nevertheless, the Douro has not abandoned its birthright.

Yet progress, innovation, and adaptation are all around us. For one thing, the home of Port has embraced a new vocation: some of Portugal’s finest table wines are now made in the Douro, ranging from the Burgundian brilliance of Niepoort’s Charme to the concentrated heft of Quinta da Gaivosa. Aside from the declining market for fortified wine, the catalyst for this revolution has been unprecedented investment into vineyards, facilities, and tourism infrastructure; interest in providing high-class tourism has exploded over the last decade as travelers increasingly seek authentic wine experiences. As a result, lavish hotels, tasting rooms, multilingual staff, new wine styles, and Michelin gastronomy are now part of the course in the Douro.

Port, regarded as the definitive example of fortified wine, took its present form around 1775. However, its roots go far deeper: the Romans were avid fans of the region, planting scores of vines along the steep slopes of the Douro in the 3rd century BC. But, as Rome’s power faltered and the empire started to crumble in 476 AD, the Douro slid into obscurity. A succession of rival civilizations, including the Visigoths and the Suebi, attempted to conquer the Iberian Peninsula. Yet the Moors established a permanent stronghold in Western Europe after their forces arrived in Andalucia in 711. Within a few years, they controlled much of Spain and Portugal.

However, a Christian reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula began in earnest in the 9th century. By 1147, Lisbon and the Douro had been liberated; Afonso Henriques founded the newly created kingdom of Portucale. And so a golden age began: a defining period of exploration and discovery as Portugal cemented its economic and political relationships with the great powers of Europe. From the perspective of winegrowers in the Douro, a seminal moment occurred in 1387, after England and Portugal signed the Treaty of Windsor. This agreement granted special privileges to English merchants who emigrated to Portugal on the understanding that they would invest in the nation’s fledgling economy. As a result, capital and expertise flowed into the Douro – Portuguese wines became the toast of England’s aristocracy in the 1400s.

Two hundred years later, tensions between France and England had reached a boiling point. The ruling English monarch, King Charles II, retaliated by banning the import of French wine. But this loss was Portugal’s gain: wine imports rose dramatically in the 17th century. In addition, the Methuen Treaty of 1703, which granted Portugal preferential taxes on wine exports in exchange for lower duty on English textiles, helped consolidate the burgeoning interest, and soon barrel after barrel was sent to the UK. Yet the wine was often spoiled by the time it reached its destination, and the shippers needed to stabilize and fortify it for the journey home. Gradually, adding spirits to the wine during fermentation became commonplace, so Port was born. Further British investment in the region soon followed, and in the 1750s, the Douro Valley became the first formally demarcated wine region in the world.

However, the latter part of the 20th century saw the region slide into the doldrums. The consumption of fortified wines had hit a wall: younger consumers lacked the enthusiasm of their parent’s generation, as ‘relaxed dining’ began to trump stuffy formality. Meanwhile, the Douro’s table wine industry was not in rude health. Fundamental to the region’s winemaking culture is the beneficio system – this was created to balance the production of Port against vintage conditions, volumes being sold in the market, and stock levels being maintained by the Port houses. Every year, winegrowers are issued their beneficio, stipulating how much of their crop can be used to make Port. The rest of their grape production was historically sold off in bulk or made into cheap plonk for local consumption – hardly an encouragement to make premium table wines.

Yet, in the 1950s, there were whispers about the potential for making high-quality unfortified wines in the region. The first pioneer was Fernando Nicolau de Almeida of Ferreira, who made Barca Velha – beloved of Jose Mourinho – in 1952. Then nothing much happened for decades until Douro table wines were given their own classification (DOC) in 1979. Fernando’s son João introduced Duas Quintas, but Douro premium table wines were few and far between. Only at the start of the early 1990s did interest in producing fine red wines take off – the Bergquists, owners of Quinta de la Rosa, started making their wine in 1991. That year, legendary figure Dirk Niepoort made the first vintage of Redoma, which remains one of Portugal’s finest red wines today.

Suddenly, an explosion of interest in making premium table wines took hold, affecting established Port houses and grower families who decided to go it alone. A quality table wine industry in the Douro was born – today, over 45% of what is produced in the Douro is sold as unfortified still wines rather than Port. “The growth in the production of still wines in the Douro is very positive for the region, firstly because it has contributed to increasing its visibility throughout the world, and also because it positions the Douro as a region with a wider range of products,” says Carlos Alves, director of viticulture and enology at Sogevinus.

He adds: “The Douro is no longer seen only as the origin of Port wine but as a versatile wine region, capable of producing wines with very diverse characteristics that adapt to different consumer profiles and consumption moments.” More than 2,500 hectares of vineyards have been replanted as part of a major investment program, typically with one or two approved varieties, as opposed to the chaotic – if charming – field blends of old. Just as significant, new styles of Port, like Taylor’s Chip Dry White Port (now available in can format), have taken the global market by storm. Once so fragile, the Douro’s economic climate is looking more robust.

The Douro Valley is one of Portugal’s most celebrated UNESCO World Heritage sites – an Instagram paradise for gastronomes and oenophiles. Indeed, there can be few wine regions more scenic and alluring than the home of Port.

And yet, some would argue that this corner of Portugal is the viticultural equivalent of Dante’s Inferno! Make no mistake, the climate is extremely harsh, with torrid summers and cold winters. In July and August, temperatures can soar above 40 degrees centigrade; mosquitoes thrive in such conditions, so the villages were built high above the river, away from the historic threat of malaria. However, the vine is one of the few species of flora that can survive the Douro’s intense summer heat, provided the plants’ roots can reach the moisture stored deep in the subsoil.

Cultivated on free-draining metamorphic schist, there is, nonetheless, a wide variety of climats (vineyard sites) in Douro, largely because elevation and aspect vary so dramatically. “The Douro has unique conditions for the production of still wines, both in terms of the soil – not very rich soil, essential for the vine to produce a balanced amount of grapes – and the climate, the protection given by Marão and Montemuro mountains create a micro-climate of their own,” agrees Carlos Alves

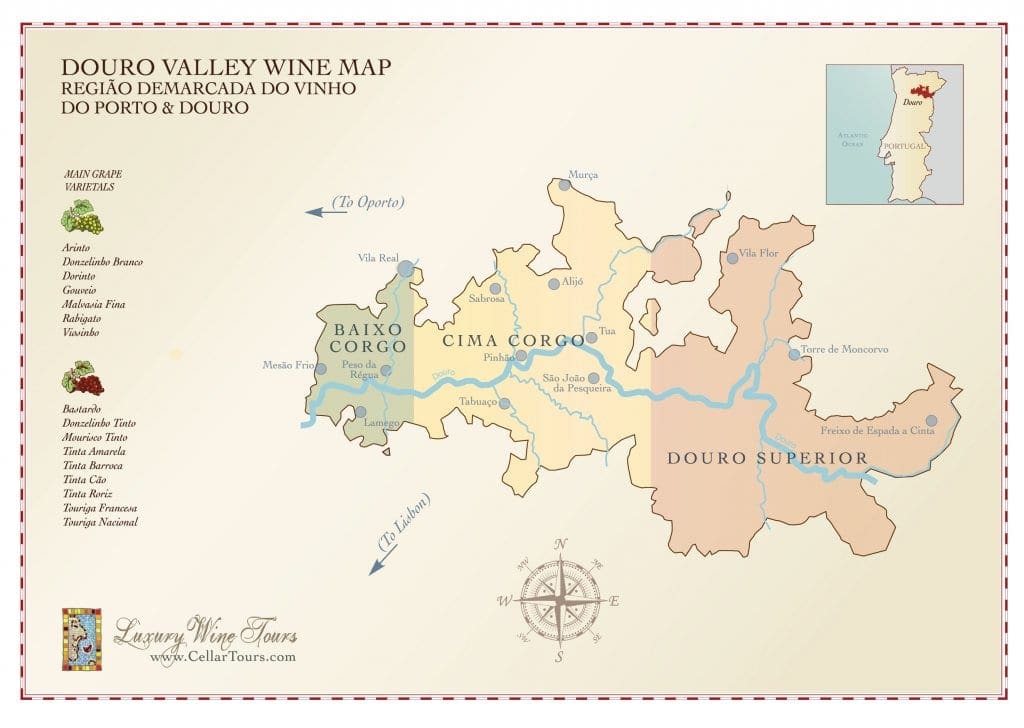

Today, approximately 40,000 hectares of vines are planted in the region, although only 26,000 hectares are authorized for Port production. The wider region is split into three subzones: the Baixo Corgo (Lower Corgo), Cima Corgo (Upper Corgo), and the Douro Superior (Upper Douro), an enormous region that runs from Pinhão to Barca d’Alva. It is said that Baixo Corgo is too damp to produce high-quality Port, albeit climate change has engendered a rethink over the past decade; it is highly suited to table wine production due to the cooler conditions. However, the Serra do Marao stops the Atlantic rain clouds from depositing their moisture in the vineyards of Cima Corgo, situated east of Baixo Corgo.

This is the heartland of Port production, especially the vineyards above and around the cute town of Pinhão. Several tributaries, including the Tua and Tedo, are increasingly used to grow white grapes for table wine production. Due to the higher altitude, the best sites benefit from diurnal temperature variation. Higher vineyards, wherever they are, tend to ripen later and produce lighter wines. At the same time, those that face south and/or west are bathed in sunlight – potent alcohol comes all too easily to winegrowers in the hotter parts of this region. For some, that is a constant worry.

Finally, we arrive at the so-called Upper Douro or Douro Superior. This is the aridest and easterly part of the Douro, a subregion with a fiercely continental climate. However, old vines can yield incredibly perfumed and concentrated reds with a beguiling complexity. Suffice it to say white grapes can struggle to maintain their acidity in this part of the valley. But, as ever, site selection is key.

For centuries, winemakers have been perfecting and honing their craft: the production of the world’s greatest fortified wine. Making Port, especially a vintage Port, is a process that takes time and effort. However, much of the most important work occurs in the vineyard. Each site is classified, from A down to F, according to factors like altitude, vine age, and orientation. The higher the classification, the more money will be paid for the grapes – these exceptional raw materials are used to produce the finest Ports, such as Quinta do Noval Nacional.

Historically, many of the best Ports were made in a very traditional way. The grapes were placed in lagares (concrete baths) where teams of men and women would tread the grapes for several days, with music played to entertain the foot stompers! This method of kickstarting – literally – the fermentation offers several advantages: tannin, color, and flavor can be extracted quickly, while the naked foot will not damage the pips, which would make the juice bitter if they were crushed. But, the advent of modern technology has meant that foot stomping is often used to entertain tourists. Today most Port producers, or shippers, employ an autovinifier, a specially adapted closed vat that pumps wine over the cap (floating skins). Nevertheless, some of the most expensive Ports are still treated to old-fashioned treading in lagares.

After the juice has been fermenting for several days, it is transferred (while still containing at least half its sugar) to a separate tank. A certain volume of grape spirit is added, which arrests the fermentation. The resulting wine is strong and sweet; however, it is not yet Port. That requires a period of aging, which traditionally took place in the Vila Nova de Gaia district in Oporto. Many great Port wines are matured in these historic cellars, although certain quintas (estates) in the Douro now age their bottles at source.

One of the best value styles is Tawny Port, matured in barrels for anything from two to fifty years. Ports labeled as Colheita (harvest) are tawnies from one vintage – the best examples are aged in wood for decades, which allows a mosaic of Tertiary flavors to develop. Indeed, some connoisseurs prefer the oxidative nutty elegance of Colheita Ports to the intense richness of vintage expressions. However, vintage Port is still held up as the pinnacle of superlative quality in the Douro. Mature examples can rival top Bordeaux in their incredible depth and power. In addition, they have a fragrance and richness that is incomparable in the world of fine wine.

The ‘compromise’ between luxury and entry-level is Late Bottled Vintage (LBV) category. These Ports, made from lesser wines in good years, are aged in barrel for four to six years. The best offer tremendous value, although they seldom reach the dizzy heights of the genuine article.

From one perspective, the Douro’s wine industry is in rude health. Its key stakeholders are a pragmatic group of people willing to evolve – and adapt – to cater to new audiences. Of course, tradition and heritage still prevail, but Port shippers understand that the category’s traditional customer base is aging and dwindling. Moreover, millennials need an extra incentive to discover Port. So although there is a concerted effort to protect and expand the market for this iconic wine style, Douro producers have added a second and third string to their bow over the past couple of decades: high-quality table wines and new styles of Port.

Graham’s White Port has proved to be a major big hit, while rosé Port is flying off the shelves. The Fladgate Partnership pioneered the introduction of a Croft rosé Port to the market – a host of copycat brands followed, including Offley Pink Port, Porto Cruz Pink, and others. They are beautifully soft and fruity wines – served chilled, they offer the ideal foil for various seafood dishes. Or, of course, the obligatory summer aperitif.

Meanwhile, the region’s tourist infrastructure has recently changed out of all recognition. Ten years ago, one was greeted by a selection of beautiful yet dusty and fusty wine estates, where visitors were only welcomed with open arms if they promised to buy a year’s supply. Yet today, Cockburn’s, to cite just one example, is now home to a shiny new visitor center to match its slick counterpart (and restaurant) at fellow Symington house Graham’s. In 2010, the group had five people working in tourism; today, it has over 50, spanning Russian, Polish, and Japanese speakers.

Calem also opened a new €3 million, 3,000 sq m visitor center in 2017, to which the Sogevinus-owned lodge has aspirations of welcoming 300,000 guests a year. The combined effect of all this is positioning the Douro at the top of Europe’s list of wine capitals. No longer the preserve of wine obsessives, the Douro appeals to all in search of beautiful scenery, excellent gastronomy, and exquisite fortified and table wines.

So what’s the problem? In two words: climate change. Recent vintages have been unbelievably dry, even by the standards of the Douro. This inevitably results in meager yields and inflated grape prices. Moreover, according to Jancis Robinson MW, a chronic labor shortage in the valley led to companies like Symingtons investing in automated picking technology. Yet the overriding concern is managing the dual challenges of prolonged drought and excessive heat/sunlight. Several options present themselves: planting varieties more resistant to heat, such as Alicante Bouschet and Gouveio, covering the vines with kaolin and silicon (they help to block harmful solar radiation levels), and the move into high-altitude winegrowing. The fight is only just beginning. But, hopefully, it’s one that the Douro can win.

Learn about the unique characteristics of Gouveio, a grape variety used in the production of Port wine. Explore its flavor profile and history in our comprehensive guide.

Find out moreThis white grape variety produces aromatic wines with floral notes and a hint of sweetness, known for its versatility.

Discover the unique and versatile Rabigato grape, and learn about its history, characteristics, and food pairings.

Find out moreLearn all about the Vioshino grape, its rich history, unique flavor profile, and food pairings. Don't miss out on this exciting grape variety! 🍇🍷 #VioshinoGrape

Find out moreDiscover Sezão, the dark-skinned Portuguese grape used in port and table wines, boasting rich flavors and a captivating history. 🍇🍷

Find out moreTinta Amarela, aka Trincadeira, is a red grape used in Port and red wine. Thrives in dry, hot climates, flaunting purple-skinned allure but susceptible to rot.

Find out moreTinta Barroca is one of the most common red wine grapes grown primarily in the Douro region in northern Portugal.

Find out moreDiscover the versatile grape: Spain's Tempranillo, and in Portugal, Aragonês and Tinta Roriz (Douro Valley). Embrace the rich cultural tapestry of this beloved varietal.

Find out moreUncover Tinta Cão, the treasured Portuguese red wine grape. A vital Port Wine blend, embodying Portugal's winemaking legacy with grace.

Find out moreIs a red grape variety known for producing wines with intense color and aromas of dark fruits and flowers. It's often used in Port wine blends and can also make complex, full-bodied still wines

Touriga Nacional red varietal is a dark-skinned grape predominately grown in Douro and Dão. In the Douro, it is used as a blending grape in Port wines.

Find out moreThere is no such thing as a poor meal in the Douro Valley. Fresh, seasonal ingredients are one half of the quality equation – the other is culinary techniques that have stood the test of time. So marvel at the landscape, sip white Port, and peruse the menu. You might find Bacalhau à bras ( salt cod served with scrambled eggs, black olives, and fried potatoes) or roast goat served with oven rice. If things turn chilly, Rojões à moda de Cinfães (pork meat fried and served with fried potatoes and blood sausage) is a robust pairing to LBV Port on a fall evening. But regardless of your choices, rest assured that the highest standards of hospitality will prevail.

If you would like us to customize an exclusive luxury tour, contact us and let us know your travel plans. We offer luxury food and wine tours for private groups of a minimum two guests. In addition, all of our private, chauffeured tours are available year-round upon request.