Trentodoc Sparkling Wines: Italy’s Mountain Metodo Classico

June 5, 2025

Explore the unique qualities of Trentodoc sparkling wines, known for their elegance, precision, and freshness. Discover why they stand out.

By: Sara Porro / Last updated: December 15, 2025

In the northeastern part of Friuli Venezia Giulia, there are the rolling hills that locals call “Collio” on the Italian side and “Brda” on the Slovenian side. While the line dividing the two countries is almost invisible, this was once the front line of the First World War, and later a tightly policed border between Italy and socialist Yugoslavia until Slovenia’s independence in 1991.

As wine journalist Fabio Pracchia wrote in Cook.Inc 36:

“Many farmers tell of elderly people who, over the course of a single life, were citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, then Italian after the First World War, then Yugoslav after the fall of Nazism, and finally Slovenian after the collapse of the Soviet bloc – all without ever moving house.”

It is in this region, shaped by shifting borders and stubborn rural traditions, that a radical idea took root: the revival of skin-contact white wines, long before the world started calling them “orange.” In a region best known to outsiders for pale Pinot Grigio, these golden, structured, rebellious wines invite a different kind of discovery.

Orange wine is made from white grapes fermented like a red wine: the juice stays in contact with skins and seeds for days, weeks, sometimes months. In Friuli, the grape varieties involved are mostly Ribolla Gialla, Friulano, Malvasia Istriana, and Pinot Grigio. Skin contact brings deeper colour (from gold to amber), light tannins, and flavors that move toward dried apricot, citrus peel, tea, herbs, and nuts.

A quick technical clarification: all orange wines are macerated whites, but not all macerated whites qualify as orange: short, light macerations yield results closer to classic whites. This matters in Friuli, where the term “ramato” has a specific meaning: traditionally, it refers to Pinot Grigio with brief or moderate skin contact, producing a copper hue (hence the name); today, the term is sometimes used more broadly.

A final distinction is cultural rather than technical. Several Friulian producers resist the label “orange wine,” arguing that they are simply making white wine as their grandparents did, before industrial winemaking pushed everything toward pale, rapid fermentation.

Long before modern winemaking began, separating white juice from skins at the press, fermenting white grapes with their skins was widespread in many winegrowing regions. Georgia is the place where this process is most clearly documented, thanks to the use of qvevri – large clay vessels buried underground, designed for fermenting and ageing wines with extended skin contact.

Archaeological work in the wider Caucasus region shows how viticulture persisted through the “Pontic refuge”, a zone that remained above water after the last glaciation and preserved wild vines.

For Friuli, the turning point arrived through Joško Gravner. Already an established grower in Oslavia, he spent the 1980s pursuing international-style whites. By his tale, his 1987 visit to Napa Valley was a turning point: the wines he tasted there, produced with advanced technology, were too similar to his own. The experience led him to question how much standardisation came from technique, and whether technology was stripping wine of its human and agricultural roots.

That same year, he started dreaming of visiting Georgia – a trip that would not happen until 2000. But already before that, in 1997, Gravner began testing with a small 250-litre Georgian amphora. Eventually, in Georgia’s wine region of Kakheti, he discovered the use of qvevri for fermenting white grapes on their skins, producing amber wines. He brought the idea back to Oslavia and adopted amphora fermentation.

The initial reaction was sharp. Much of the Italian wine establishment did not understand the move. Critics, accustomed to technological precision and pale, rapid-fermented whites, judged the shift harshly; Gambero Rosso, then Italy’s most influential wine and food magazine, even ran a stern editorial calling it an “involution”. Yet Gravner’s choices catalysed a new direction. Neighbours, including Stanko Radikon, Dario Prinčič, and Damijan Podversic, began exploring extended maceration with their own varieties, transforming Oslavia into a focal point for a style that would later be imitated worldwide.

The revolution had deep historical undertones. In the decades after the Second World War, labour shortages and limited equipment meant that many growers made white wine by letting the grapes ferment with their skins, since there was no practical way to separate the skins earlier. It was not a stylistic choice but the everyday logic of rural winemaking.

Then, starting in the 1950s, industrial winemaking was adopted in Friuli. Aided by measures such as temperature-controlled steel, selected yeasts, filtration, and new cellar technology, stability and cleanliness were achieved. At the same time, this shift marked a break with agricultural traditions. It led to the production of pale, fast-fermented whites and international varieties, the opposite of the older “fare il bianco” (“make the white wine”) approach.

By the 1990s, some Friulian producers had already begun reviving the traditional ramato Pinot Grigio, fermented with moderate skin contact. But a fundamental shift came in the early 2000s, when Gravner and Radikon began pushing maceration to its limits, taking what had been a rural tradition into a modern philosophy of wine.

While Gravner and Radikon were reinventing skin-contact whites in Oslavia, the broader Collio area continued to build its reputation on clean, cool-fermented whites that had shaped the region since the 1960s. For decades, the long-maceration wines emerging from Oslavia sat outside that model. Many producers chose to declassify their bottles, since deeper colour and extended skin contact did not conform to DOC standards.

This gap between traditional practice and formal regulations has only recently begun to close. The Collio Consorzio has introduced the category “vino da uve macerate”, requiring a minimum of seven days of skin contact and applying colour and volatile-acidity thresholds similar to those used for red wines. The move is interpreted in different ways: for some, it is overdue recognition of a tradition rooted in Friuli’s hills; for others, it signals an attempt by Collio to formalise its role as Italy’s leading region for orange wines, a status built over decades of experimentation in Oslavia and its immediate surroundings.

The groundwork laid by Gravner in Oslavia shaped much of what followed; the estates below represent how that legacy spread across the same hills to neighbouring wineries and beyond.

The Radikon family began full-skin-contact vinification in 1995 and stopped using sulphur in its wines in 2002. They farm organically on ponca marl, the mix of clay and sandstone that defines Collio’s hillsides, and age their wines for years in large Slavonian oak. Their Ribolla and Jakot serve as reference points, while the younger S line offers an accessible entry into macerated whites. Read more

Often described as Oslavia’s rebel duo, they share a hands-on, almost ascetic approach to farming – Prinčič famously works barefoot in the vines – and a cellar style built on long macerations, low or no sulphur, and no filtration. Their wines show how skin-contact whites can be both wild in texture and precise in structure. princicdario.com | damijanpodversic.com

On the limestone plateau above Trieste, facing the sea and swept by constant winds, Kante works with Vitovska and other local whites. His measured use of skin contact offers another facet of Friuli’s macerated-white culture, just beyond the borders of Collio. Read more

Friulian orange wines range from lightly grippy and saline, sometimes with a clear seaside character, to dense, tea-like bottles with serious tannins, closer to a red. Flavors often include dried stone fruit, citrus peel, chamomile, wild herbs, and nuts, with occasional gentle oxidative notes when aged in large, old casks.

Ageing is central to the region’s approach. Many top examples are built to evolve for 10 to 20 years. Radikon’s 1-litre bottles were designed to support slow ageing. Gravner – being Gravner – pushes this even further: since the 2007 harvest, his wines have aged for 7 years before release, which he considers the minimum time needed before they are ready.

Travellers will often encounter both ends of the spectrum. A young, macerated Ribolla poured in a casual osteria shows freshness and grip. In contrast, an aged bottle, tasted at the winery or in a more high-end restaurant, will reveal the depth that extended maceration and long ageing deliver.

Where to Focus: Two Key Zones

Rolling Ponca Hills on the Italy–Slovenia border, shaped by WWI history and home to the highest concentration of Friuli’s skin-contact pioneers. Base yourself in Cormòns or Gorizia.

Sea winds sweep the limestone plateau above Trieste. Here, Vitovska, Malvasia Istriana, and other whites gain a more saline, chiselled profile when made with skin contact.

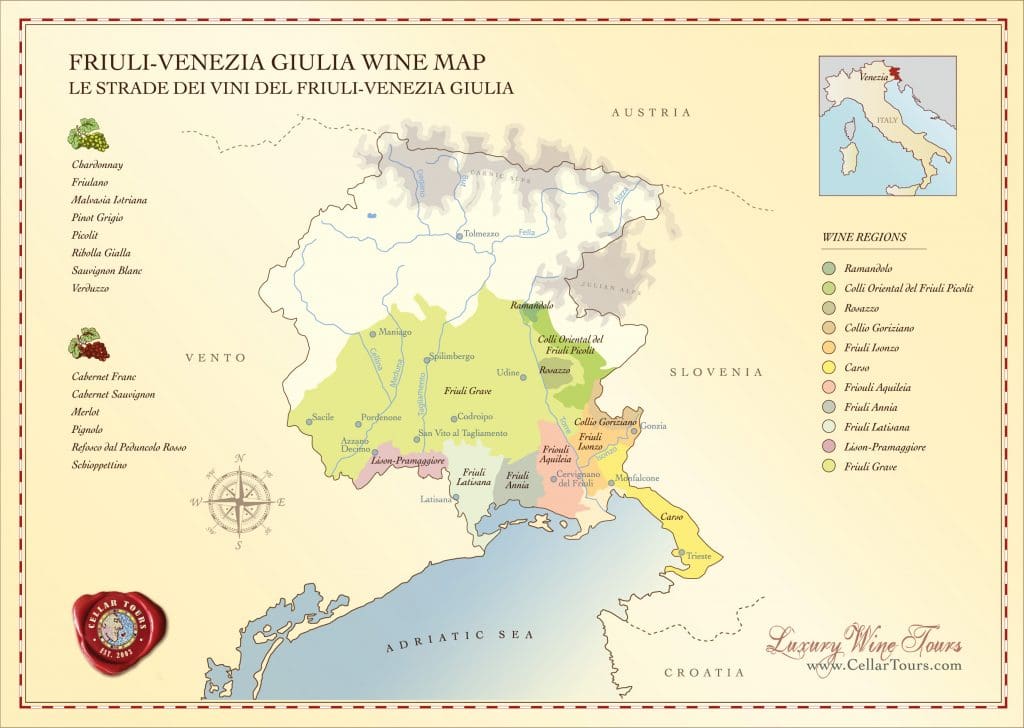

Regions: If you see Collio, Collio Goriziano, Friuli Colli Orientali, Carso/Carso-Kras, or Venezia Giulia IGT, you know you’re in the right place. Brda in Slovenia is Collio’s twin.

Grapes & keywords: Ribolla Gialla, Friulano, Malvasia Istriana, Pinot Grigio (ramato). Look for “macerato”, “macerazione sulle bucce”, “vino ambrato”, “ramato”, “orange”.

DOC vs IGT: Not a quality ladder. Many key producers use IGT or simple vino bianco because older DOC rules excluded extended maceration.

New Collio “macerato” category: If the label says “Collio macerato”, it underwent a minimum of 7 days of skin contact. A plain Collio DOC with no such wording is usually a classic pale white. Read more of the official Collio website

Back-label clues: Alcohol 12.5–14%, colour from gold to amber. Terms like “unfiltered”, “low sulphur”, and “amphora/qvevri” point to a more natural style.

What to say: Just ask: “È macerato?” and let the producer explain.

Orange wines pair naturally with classic Friulian gastronomy. Frico is the classic pairing: a crisp pan-fried potato cake with Montasio (a traditional cow’s milk cheese). Other notables include local salumi, such as prosciutto di San Daniele, pitina, soppressa, and traditional neck and belly cuts. —along with aged Montasio, wild-herb dishes, hearty pasta, and, near the coast, simple Adriatic fish.

Their tannin and acidity let them move easily between mountain and sea, ideal for mixed menus and shared plates.

These wines are best enjoyed at around 12–14°C – not straight out of the fridge. When it comes to glassware, you could stay pragmatic: different shapes suit different structures and tannin levels. Gravner, however, serves his wines in a stemless borosilicate cup inspired by Georgian drinking vessels. Your hand wraps around the cup in a gesture that feels warm, almost symbiotic, and gently warms the wine.

When Luigi “Gino” Veronelli – one of Italy’s most influential food and wine writers, whose work championed rural knowledge at a time when industrialisation was eroding it – called Joško Gravner “the first winemaker in the world”, he was pointing to a way of thinking about wine that placed agriculture above technology and market logic. Friuli would soon confront this dualism itself.

The shift from rural farming to industrial winemaking brought a dramatic rise in quality, enabling Friuli to overcome the inconsistencies of peasant production. No one longs for the volatile, unstable wines of that era.

Yet the same tools that raised quality also encouraged standardisation. Fertilisers, international varieties, and filtration: these choices helped Italian wine speak to global markets. They made sense in a world hungry for reliability and volume. But wine is not subject to the same imperatives as staple crops. Now that consumption is shrinking, wines without identity or a sense of place – wines that could come from anywhere – make less and less sense to produce.

It is in this context that Friuli’s macerated whites gain their meaning. Producers like Gravner did not reject technology in favour of nostalgia: the reintroduction of fruit trees between the rows; the installation of nesting boxes to promote the return of bird species; the creation of and small bodies of water near the vineyards were not gestures of romanticism but a deliberate move away from monoculture, which is now recognized as fragile in agronomic and ecological terms. Long maceration and extended ageing were part of the same rethinking.

In this way, orange wine becomes a way of looking at Friuli: a region asking itself what kind of agriculture it wants to practice, what forms of knowledge it wants to preserve. Friuli is neither the utopia of natural-wine myth nor simply Pinot Grigio country; it is a place still testing the balance between technique and tradition.

For travellers and drinkers, the best approach is straightforward: choose your own Friuli. Taste the cool, crystalline whites that built the region’s reputation, then taste the macerated wines that challenge it. Somewhere between the two lies your personal definition of a Friulian white.

If you would like us to customize an exclusive luxury tour, contact us and let us know your travel plans. We offer luxury food and wine tours for private groups of a minimum two guests. In addition, all of our private, chauffeured tours are available year-round upon request.