Graves Wine Classification / Crus Classés de Graves

September 24, 2024

Learn about the 1953 and 1959 Graves Classification, Château Haut-Brion's unique stance, and how it led to Pessac-Léognan's formation.

By: Barnaby Eales / Last updated: May 2, 2025

Bordeaux produces the greatest volumes of fine wine on earth. The 1855 classification of Grands Crus, which ranked 60 prestigious Bordeaux Châteaux in the Medoc and one in Graves, along with those in Sauternes and Barsac, is the most famous of all wine classifications. Bordeaux’s coastal location helped it become the world’s most renowned fine wine region.

Discover more about Bordeaux Wine Classifications

The British and Irish developed a taste and interest in the quality levels of Bordeaux wine. England played a key role in developing Bordeaux wine and consuming claret, having imported it since the 13th century. However, it was predominantly the Irish merchants of Bordeaux in the 18th century who contributed the most to the birth of Grands Crus wines by blending the most expensive wines and selling them internationally through the port of Bordeaux.

The 1855 classification, officially formalized as a pre-existing hierarchy of fine wines based on prices, is a unique and significant aspect of Bordeaux’s wine history. More than just a price list, it has served as a benchmark and provided a deep understanding of Bordeaux fine wine for investors, collectors, and enthusiasts worldwide, underscoring its enduring relevance and historical significance.

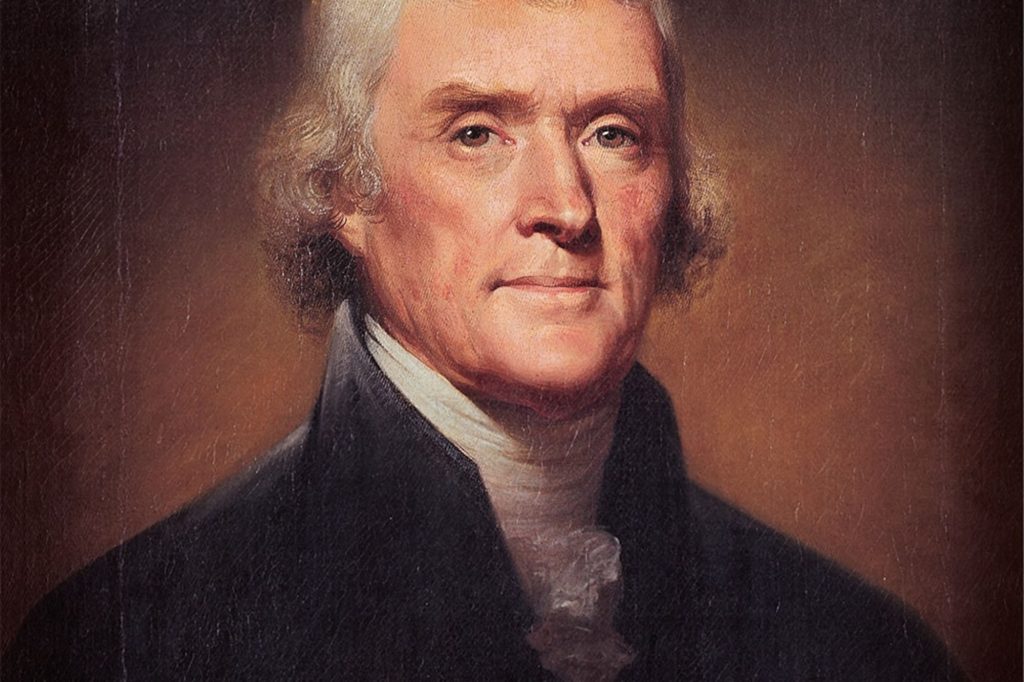

In the run-up to 1855, Thomas Jefferson, as US Ambassador to France, compiled his own Bordeaux classification list of first to third growths in 1787– a transcript of fine wine market prices made during a three-day visit to Bordeaux. In his groundbreaking 1816 book, ‘The Topography of All Known Vineyards,’ Andre Jullien, a distinguished Parisian wine merchant, laid the groundwork for the Bordeaux 1855 wine classification.

His detailed rankings and insights, echoing those of contemporaries like Thomas Jefferson, would ultimately see their top picks become ‘premier crus’ or first-growths in this esteemed classification. Wine writers André Simon, Alexander Henderson, Cyrus Redding, Wilhelm Franck, and Bordeaux merchants Tastet and Lawton drew up their wine lists in the first half of the 19th century.

Meanwhile, in 1850 Cocks, an English writer, and Feret, a French publisher, published the guide’ Bordeaux and its wines classed according to merit’, which listed first and second crus.

Five years on, the 1855 Bordeaux classification, which ranked Châteaux wine from first to fifth growths, finally came about following a request from Napoleon III’s Exposition Universelle, or ‘ World Fair,’ which was organized to showcase the best of France’s produce. Contrary to popular belief, Napoleon III did not directly order the 1855 Bordeaux classification.

Before the 1855 Bordeaux classification, the region already had established price lists for fine wines. Keen to preserve their autonomy and avoid interference from Parisian authorities, the Bordeaux wine trade formalized their own classification system.

Burgundian winemakers were also presenting their wines at the World Fair and contacted Bordeaux, wishing to present their wines together. In the end, the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce decided to do its own presentation, enlisting the Wine Brokers’ Union of Bordeaux to provide the classification of fine wines.

Bordeaux brokers were chosen to draw up the classification due to their comprehensive knowledge of wine production and the trade’s intricacies. Their status as ministerial officers, which required them to have a certain integrity, made them a trusted choice. Their involvement was an attempt to avoid power struggles between merchants (negotiants) and Châteaux (estate) owners, some of whom owned estates.

On April 18th, 1855, the brokers, acknowledging the sensitivities around classification, replied to the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce by saying:

“You know as well as we do, Gentlemen, how delicate this classification is and how it arouses susceptibilities. This is why we have not attempted to draw up an official list of our great wines, but rather to submit for your consideration a work whose elements have been identified from the best sources.“

The 1855 classification of Grands Crus Classés features a price list of five quality levels of Chateaux producing fine red wine from first to fifth growth:

It also classified Sauternes and Barsac. 26 properties producing white sweet wines were ranked according to their market value in two divisions (Premier Cru and Second Cru). However, the famous Château d’Yquem was rated so highly that it was granted ‘Premier Cru Superieur’ at the top of the classification, a ranking even higher than the famous red first growths.

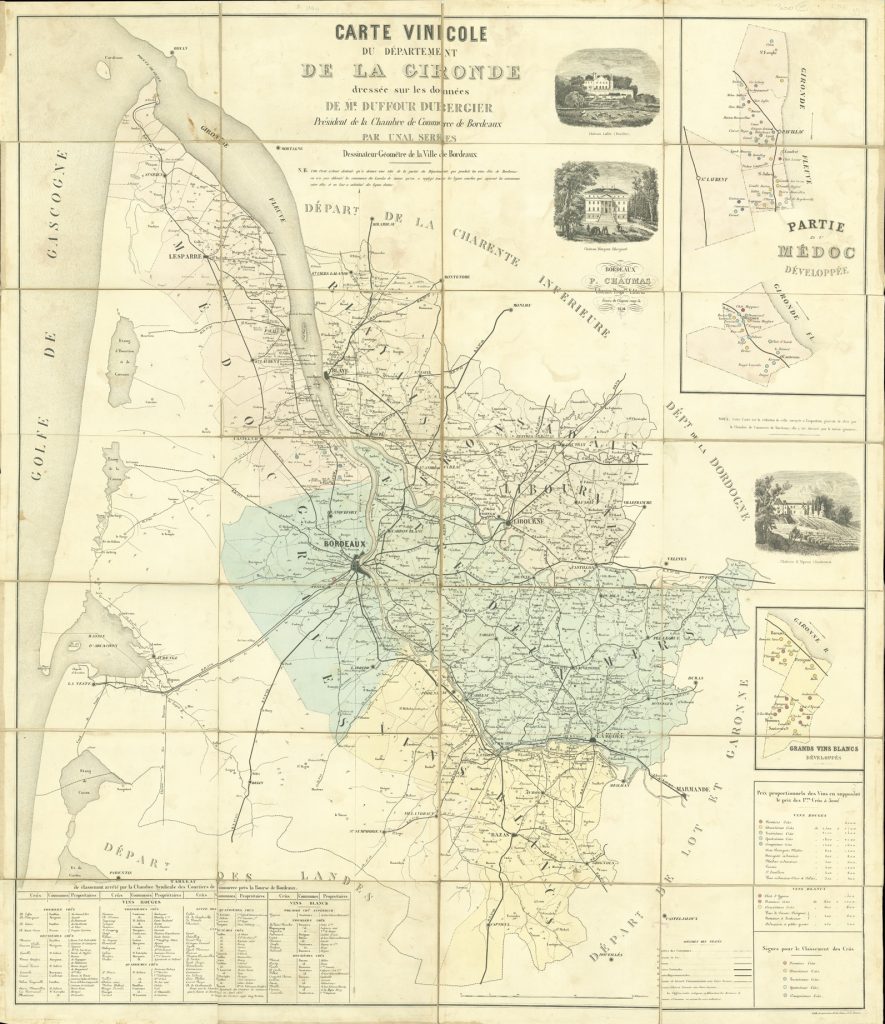

For the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1855, the newly established 1855 Bordeaux Classification was prominently featured as part of the regional display. This display included a detailed map, situating each classified wine geographically.

But as the late Dewey Markham Jr wrote in his acclaimed book, ‘1855: A History of the Bordeaux Classification’:

“There were no château visits, no requests for samples, no tastings involved in the establishment of the rankings, nor was there any need for them.“

Haut Brion in the Pessac-Léognan, a sub-appellation of the Graves wine region of Bordeaux, is the only first growth of the 1855 classification outside the Médoc. In the 17th century, Haut Brion created modern Bordeaux claret and brand awareness by opening the Pontac’s Head tavern in London in 1666, named after Haut Brion’s owner, Arnaud de Pontac. Bordeaux fine wine became synonymous with Pontac rather than the name Haut Brion.

Name recognition of the four first growths, Haut Brion, Lafite (now known as Lafite-Rothschild), Château Margaux, and Château Latour, had come about from the quality of their wines, allowing them to sell them to British drinkers, at much higher prices than other Bordeaux wines.

Since 1855, these Châteaux (and Mouton Rothschild, which became a first growth later in 1973) have maintained their status as first growths. The classification has allowed them to command high prices, which sustain investment and commitment to fine winemaking required to preserve their singular heritage.

This classification has significantly influenced the Bordeaux wine industry, shaping the reputation and market value of these Châteaux. It also set a benchmark for quality and price, guiding investors and collectors in their wine choices. Bordeaux producers in St Emilion and Pomerol were not included in the classification as they were out of the picture regarding prices at the time.

Mouton Rothschild wine prices reached the same levels as the first growths in 1853. However, it was ranked as a second growth as it did not have the same price record. Mouton Rothschild is known for its groundbreaking decision in 1924 to bottle all wine at its estate rather than sending barrels to negociants. That same year, it started commissioning renowned artists to create art for bottle labels.

Nearly a hundred years later, Baron Philippe Rothschild, Mouton Rothschild’s owner, enlisted Alexis Lichine, known by some as the ‘Pope of Wine,’ to promote Mouton Rothschild to first growth status. Lichine was part of a committee that pushed for revising the 1855 classification in 1961. On the verge of being accepted by France’s appellation body, the INAO, the revision was leaked to the ‘Sud Ouest’ newspaper, prompting outrage from the Bordeaux trade and Châteaux as it would have removed some of them from the classification.

The revision proposal divided the châteaux into three groups; 17 would have been relegated out of the classification, and 13 new producers would have been promoted to it.

Lichine believed the original classification had become obsolete and wanted to incorporate Bordeaux producers elsewhere than the Medoc.

Thus, the 1961 revision never came about due to the uproar it provoked from the Bordeaux trade. That’s why only Mouton Rothschild was promoted to first growth status in 1973.

The inclusion of Château Cantermerle in the Grands Crus Classés as a fifth growth was the only official change since the inception of the 1855 classification. Cantermerle had been left out of the classification despite having obtained eligible prices. Until a year before the 1855 classification, Cantermerle had been directly selling its wines to clients rather than using brokers, so it had been left out. Protests from Cantermerle’s determined owner, Catherine de Villeneuve, who provided evidence of her sales prices over 40 years, ensured that the Château was included in the classification in September 1855.

The price approach is unique to Bordeaux. Indeed, in the same year, 1855, a detailed map of Burgundy classified several hundred different vineyard sites. If it weren’t for the happenstance of the 1855 classification, Bordeaux’s classification may have been based on vineyards and terroir. In the 1855 Classification, the name of the Château was classified rather than the vineyards or terroir. This allowed the Châteaux to buy land and expand their vineyards as long as the land was in the same appellation as the Château.

Today, much talk is about the famed gravel mounds where the Médoc’s best châteaux are located. Still, the trading of land does not affect the classification rankings of Châteaux, showing just how vineyards and terroir were irrelevant to the 1855 Classification.

In 2009, Liv-ex, the London International Vintners Exchange, the global marketplace for the wine trade, recreated the 1855 classification by ranking major Left Bank wines by their price on the secondary market.

In essence, it wanted to create the classification that would have been drawn up if contemporary prices were prevalent in 1855. Liv-ex’s regular market updates on Bordeaux show how, in many cases, prices no longer correspond to the classification.

Given today’s prices, it is estimated that only about a third of the 61 classified châteaux would retain their original pricing tiers. The first growths would remain at the top, and many fifth growths would stay at the bottom, but there is extensive reordering between other rankings.

Several wine pundits argue that the 1855 classification is an anachronism: it is viewed as none other than a freeze-frame of the status of Châteaux at that time.

The classification, global recognition, and heritage impact have given the top Châteaux an advantage over other Bordeaux producers.

There is what is known as a glass ceiling for the renowned first growth, which keeps them above other Châteaux in terms of prices and prestige.

The market reality of pricing has drifted far from the 1855 classification, as reflected in the emergence of ‘Super Second Growths’—wines, which, due to the deep pockets of investors who have bought Châteaux, sit between first growths and second growths in terms of price but compete with first growths in terms of quality. Amongst them are Château Palmer, a third growth, and Lynch Bages and Pontet Canet, both fifth growths.

A key part of the heritage of Bordeaux fine wine, the Bordeaux wine trade uses the 1855 classification as a promotional tool worldwide. It has been key in propelling Bordeaux wine to international recognition as a reference point for new markets such as North America in the 20th century and later Asia. Some of the leading Chateaux allow tourist visits and tastings.

The 1855 Classification forces Bordeaux’s top Châteaux to live up to expectations as the forerunners of fine wines and maintain their heritage. Over the past five years, there’s been talk behind the scenes in Bordeaux of moves to officially revise the 1855 classification, which would change the second growths.

This could entail promoting Bordeaux producers to the classification and removing some Châteaux. The revision has not come about and, for now at least, seems unlikely due to conflicting interests. Yet, re-evaluation and maintaining the status quo of the 1855 classification are both problematic. Whether the classification will exist in 2055, 200 years after its inception, is another matter, but its unique legacy remains.

If you would like us to customize an exclusive luxury tour, contact us and let us know your travel plans. We offer luxury food and wine tours for private groups of a minimum two guests. In addition, all of our private, chauffeured tours are available year-round upon request.