Discover Alba, Piedmont's culinary jewel, famed for truffles and wines. Explore rich history and gourmet paradise in Italy's food and wine capital.

Read more

EXPLORE ALL OUR PIEDMONT WINE REGION GUIDE

Last updated: February 25, 2024

In the 20th century, Barbaresco played understudy to Barolo’s more famous and celebrated wines. In every conceivable aspect – reputation, quality, longevity – they were considered inferior to Barbaresco’s iconic neighbor. This is despite the remarkable energy and passion of Bruno Giacosa, who had shown that Barbaresco could have the intensity and elegance of Barolo back in the 1970s.

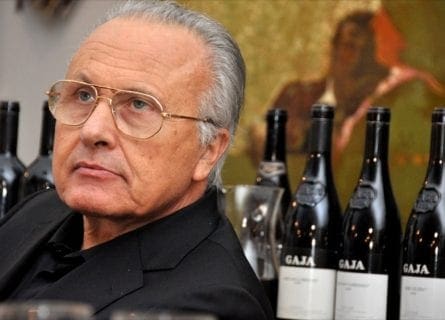

Yet consumers refused to listen. The region needed a showman – a charismatic promoter who could modernize Barbaresco’s global image. That man was Angelo Gaja: sharply dressed and smooth as hot vintage Merlot. Armed with years of experience, Gaja shook the appellation out of its inertia; he positioned his wines alongside First-Growth Bordeaux to the world’s press and critics, with prices to match! Controversy also initially surrounded his decision to import new barriques and international grape varieties to the vineyards of Piedmont – many have since followed Gaja’s example. The region owes him a great debt of gratitude as Barbaresco continues its wild ride into fame and fortune.

Piedmont bristles with history – it is Italy’s second-largest region and one of its most diverse. In the ancient era, Celtic-Ligurian tribes founded the city of Taurisia on the banks of the River Po; however, Rome was not yet a potent force in local politics. Indeed, the settlement enjoyed a peaceful existence for several centuries until the outbreak of the Second Punic War between Carthage and Rome ended the former’s hegemony over North Africa and Spain. During the conflict, Taurisia was captured and destroyed by the Carthaginian general Hannibal in 218 BC. It would be another two hundred years before the Roman colony of Augusta Taurinorum could take its place.

However, Rome’s authority weakened in the 4th century as rival civilizations became ever more ambitious in their plans to conquer Western Europe. Eventually, the entire Western Roman Empire descended into chaos, creating a power vacuum that many were eager to fill. Augusta Taurinorum was attacked numerous times during this period (historians refer to it as the ‘Dark Ages’), not least by the Goths, Franks, and Lombards. The latter has been the subject of many fascinating historical studies: their ethnogenesis occurred in northern Germany, yet by the 6th century, they had conquered most of the Italian Peninsula. Their reign ended when the papacy summoned the Franks to drive the Lombards out of Italy in the 700s. After this had been achieved, the Catholic Church crowned the Frankish king Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor in AD 800.

In the Middle Ages, Piedmont became one of Western Europe’s most wealthy and cultured regions; viticulture thrived on both sides of the River Tanaro. However, the term ‘Nebbiolo’ only appeared in written documentation in the late 1700s. Two centuries earlier, the powerful House of Savoy abandoned their capital of Chambery to set up a court in Turin. After the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, Northwest Italy came under the control of Austria and Russia before Vittorio Emanuele I restored the House of Savoy in 1814. During the 19th century, a group of winegrowers founded the Cantina Sociale di Barbaresco – its remit was to establish a distinct reputation for the wines of Barbaresco, as most of the grapes were sold to Barolo producers in the 18th century.

Yet until the 1850s, Barbaresco was renowned for its sweet wines, vinifying Nebbiolo without concluding the fermentation and bottling with a high degree of residual sugar. This all changed when a French winemaker called Louis Oudart was recruited by a landowner in Barolo. He demonstrated how to make dry styles – his ideas spread like wildfire. Soon, the Oudart paradigm became firmly entrenched in the mindsets of Barbaresco’s producers; Nebbiolo was handled with the care and attention given to the best Pinot Noir vineyards of the Cote d’Or. Nevertheless, the appellation has long suffered from unfavorable comparisons with its more famous sibling. This intransigent view remained unchallenged until Angelo Gaja shook the world out of its inertia, and Barbaresco has not looked back since.

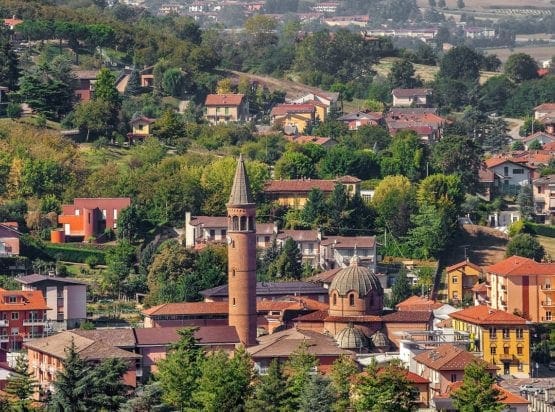

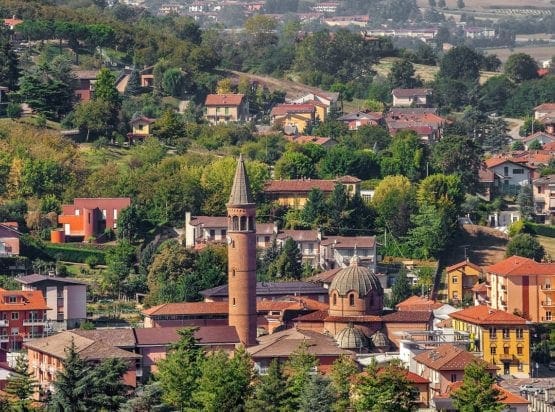

The ethereal red wines of Barbaresco are made in the Langhe hills of northwest Italy, situated on the right bank of the River Tanaro. The vineyards are found northeast of Alba, surrounding the villages of Barbaresco, Neive, and Treiso. Barbaresco is undoubtedly the most pretty: located on a ridge facing west towards Alba, it is flanked by a series of remarkable terroirs that fetch the highest prices. The vines are cultivated on well-drained calcareous marls and, like Burgundy, the best sites enjoy a south-facing aspect with moderate altitude; Nebbiolo is an exceptionally late ripener, so the finest wines tend to come from vineyards not higher than 300 meters.

However, the vineyards of Barbaresco are generally slightly lower and warmer than those of Barolo, partly due to the somewhat maritime climate and hotter summer temperatures. As a result, the harvest in Barbaresco will often start two or three weeks earlier than in neighboring Barolo, where growers are still tending to their vines.

But despite a resurgence in the 20th century, Barbaresco still has less than half as much vineyard as Barolo and produces fewer bottles of wine. That said, there is a clutch of vineyards that both critics and consumers regard as Barbareso’s unofficial ‘Grand Crus.’ Indeed, collectors swoon over Asili, Martinenga, and Sori Tildin – they benefit from perfect drainage, slope, and aspect, with old vines producing wines of remarkable concentration and purity. Moving lower and to the east, the vineyards surrounding Neive are slightly less fine if still in the top ranks of Barbaresco. The finest terroirs in Neive include Bricco di Neive and Santo Stefano, benefiting from ideal sun exposure and perfect drainage. The best wines from these sites are exceptional: concentrated and powerful, with enough stuffing and tannic structure to last nearly as long as the best Barolos.

Moving southwest, we find the commune of Treiso, whose Nebbiolo tends to be lighter in structure and very aromatically expressive. Pajore and Roncagliette are among the best climats. Like Barolo, Barbaresco is split into subzones. However, everyone is hesitant about committing to a hierarchical terroir classification in the Burgundy mold despite the introduction of the Menzioni Geografiche Aggiuntives in 2007.

Nebbiolo, of course, remains the signature grape of both regions; however, it doesn’t have a monopoly on viticulture in Barbaresco. Growers realized long ago that the highest slopes would not ripen Nebbiolo; instead, they planted Dolcetto, which ripens into a gloriously soft and approachable wine in the best years. There are also smatterings of Moscato and Barbera, both of which make excellent wines. Angelo Gaja even planted Cabernet Sauvignon in Barbaresco, convinced that the terroir could do the grape justice. He has been vindicated – Darmagi (a Bordeaux blend) is arguably one of the finest reds in Piedmont.

Until the 1980s, producers in Barbaresco adhered to a fairly straitjacketed paradigm laid down by Louis Oudart in the 19th century. Most importantly, every bottle marketed as Barbaresco was a 100-percent Nebbiolo wine; this is still the case today, and there are no exceptions. He also advocated a late harvest, lengthy fermentations (typically in beech or chestnut vats), and extended extractions, finishing with maturation in wooden casks, sometimes for as long as a decade. These ‘rules’ remained unchallenged until Angelo Gaja started embracing shorter maceration times, gentler extractions, and aging in New French oak – the latter horrified the traditionalists. Nevertheless, the formula established by Oudart could yield fiercely tannic red wines that never shed their austerity; even mature Barbaresco could be endowed with incredibly dry and astringent tannin. The poor fruit was never given a chance to emerge!

However, with a few notable exceptions, overall winemaking standards in Barbaresco have risen dramatically, with far fewer grapes sold to cooperatives and local merchants for anonymous blending. Meanwhile, the costly single-vineyard wines of Gaja – such as Costa Rossi – often outperform their counterparts from Barolo in the auction circuit. They are produced in a way that appeals to contemporary audiences: modern vinification philosophies have not achieved complete hegemony in Barbaresco; however, they are very popular. Thus, most growers chase phenolic ripeness, fermentation in stainless steel, shorter macerations, and aging in either new or older French oak. Protecting the expression of fruit is now key in Piedmont, and its continued global success relies on this.

Barbaresco is also typically released after two rather than Barolo’s three years of aging, and the wines are undoubtedly more approachable and less tannic than top Barolos. Yet this is only to their advantage – claiming that Barbaresco is less fine would be disingenuous. With a few years of bottle age, the same intoxicating aroma fills the glass: tar, violets, forest floor, wild mushrooms, raspberry, and leather—pure bottled magic.

When delving into the glorious red wines of Barbaresco, it is very tempting – and perhaps indecorous – to present the appellation as a one-man show. Yet, while we do not wish to play favorites, Barbaresco’s winemaking community owes much to the Gaja family. After the region was awarded DOGC status in 1980, Barbaresco was relegated to the status of “a decent value alternative to Barolo” – hardly a ringing endorsement. The wines made across the zone were often excellent. However, critics and buyers were reluctant to view the neighboring appellations as equals. It was pure, unadulterated prejudice: the grape variety is identical, and many of the sensory qualities of Barolo are closely emulated in the vineyards northeast of Alba. But people would not be swayed.

That is until Angelo Gaja strode onto the stage and captured our attention with his dazzling wines. Such infectious enthusiasm did much to change attitudes, a mission now continued by his daughters Gaia and Rossana. They are among Piedmont’s most respected and dynamic winemakers, a legacy that began in 1859 and entered a new era in the 1960s after Angelo joined the family business. Planting international grape varieties and embracing viticultural techniques imported from France, Gaja was eager to show the world that Barbaresco could make wines as profound as Burgundy. The winemaking was adapted to embrace hitherto ‘sacrilegious’ ideas, and the quantities produced were drastically lowered – including selling off an entire vintage in bulk after the disastrous 1984 growing season. Suddenly, critics were proclaiming the wines of Barbaresco as “magnificent” and “among the best in Italy.”

Meanwhile, Bruna Giacosa continues the inspirational work of her late father, crafting staunchly traditional expressions of the Nebbiolo grape that peak after ten years in bottle; Giacosa’s wines have always been powerfully structured, yet the tannins do not overwhelm the hauntingly ethereal aromas and flavors. These two great winemakers may disagree about many things, but their combined brilliance has elevated Barbaresco to the ranks of a first-division wine region. No longer an understudy, Barbaresco now elicits excitement rather than apathy. Its reputation has finally caught up with reality.

Explore Arneis: A Fascinating Journey Through Piedmont's Wine Heritage from Ancient Romans to Modern Resurgence

Find out moreChardonnay is a green-skinned grape varietal native to the Burgundy wine region in France and one of the most popular varieties worldwide.

Find out moreThe sauvignon blanc grape varietal, originally from the Bordeaux region of France, is now one of the world's most loved white varieties.

Find out moreDiscover the irresistible allure of Cabernet Sauvignon—a worldwide favorite with robust, dark-bodied flavor. Unleash your wine journey today!

Find out moreMerlot is the most cultivated grape in Bordeaux and closely related to Cabernet Franc

Find out moreNebbiolo is an Italian red grape primarily linked to Piedmont, where it creates prestigious DOCG wines like Barolo, Barbaresco, and others. Its name may come from "nebbia" or "nebia," signifying the fog that envelops Piedmont during late October harvests. Nebbiolo wines are light in color but can be intensely tannic when young, offering scents of tar and roses. They develop a brick-orange rim with age, revealing aromas like violets, truffles, cherries, and tobacco.

Piedmont’s food culture is celebrated for its rich traditions and sensual flavors, equal to the gastronomy of the Cote d’Or. Truffles play an essential role – is there anything more exquisite than tagliatelle cocooned in a white truffle and Parmigiano cream sauce? Indeed, many of the best dishes are fresh, simple, and quick to prepare. Feast on gnocchi di patate di gorgonzola and pork ragu (stew), slowly braised in Nebbiolo, before sampling the obligatory torta langar ola (hazelnut cake). Bliss.

A Guide to the Gastronomy and Cuisine of Piedmont: Read more

Discover Alba, Piedmont's culinary jewel, famed for truffles and wines. Explore rich history and gourmet paradise in Italy's food and wine capital.

Read more

Visit Barolo: A medieval gem in Italy's Langhe, famed for its 'King of Wines' Nebbiolo, historic castle, and enchanting vineyard tours.

Read more

Torino: A dynamic blend of royal history, industrial innovation, and cultural vibrancy, nestled in Italy's scenic northwestern Alps.

Read moreIf you would like us to customize an exclusive luxury tour, contact us and let us know your travel plans. We offer luxury food and wine tours for private groups of a minimum two guests. In addition, all of our private, chauffeured tours are available year-round upon request.