Immerse yourself in Jerez de la Frontera's vibrant flavors and uncover hidden culinary gems with our expert insider guides. Plan an unforgettable trip today!

Read more

EXPLORE ALL OUR ANDALUCIA WINE REGIONS GUIDE

Last updated: August 15, 2024

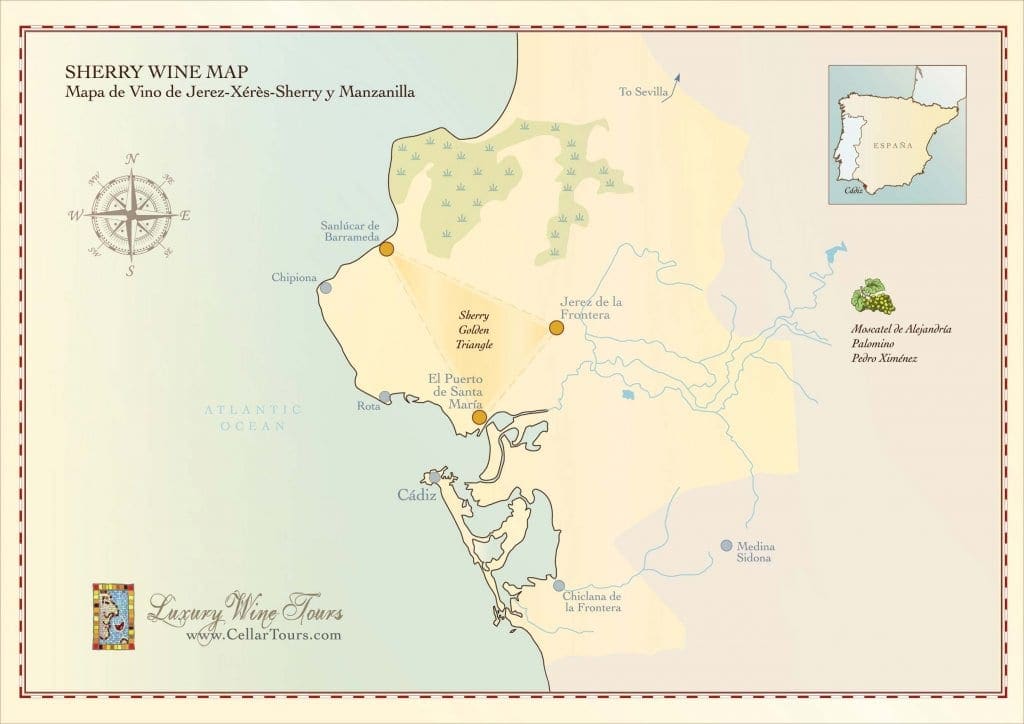

The Sherry Triangle, encompassing the towns of Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa Maria, represents Andalucia as its most seductive and alluring. It is a region of patios, guitars, flamenco dancers, and tapas bars that come alive when other cities go to bed. The town of Jerez de la Frontera, situated northeast of Cadiz, has long been its capital. Yet although Jerez lives and breathes wine as Epernay does Champagne, the production area extends far and wide to the south and east, respectively. This is the so-called Sherry Triangle: picturesque vineyards that supply the essential raw materials used to make Sherry.

But what is it, exactly? For centuries, winemakers have been adding grape spirit to wine (after its fermentation is complete) to produce this wonderful drink we call Sherry. This age-old process, known as fortification, increases the alcoholic strength of the finished product. It comes in many guises: Fino, Amontillado, and Oloroso styles work on various occasions, from apéritif to table wine to an after-dinner sip. Indeed, Sherry is the undisputed – and underrated – bargain of the fine wine world. Sadly, consolidation, closure, and takeover have meant that there are far fewer producers than 25 years ago – and less demand. But a noble crusade is being fought inside the walls of Sherry’s historic wineries as the category reinvents itself as a trendy tipple for image-conscious Millennials. The question is: are the hipsters listening?

Discover more about Spanish Wine

This corner of southwest Andalucia is a mecca for history lovers: Cadiz may be one of the oldest cities in Europe. Historians believe it was founded in 1100 BC by the Phoenicians, a tremendous seafaring civilization based in the Middle East. Their trading activities endured for centuries until the Romans invaded the Iberian Peninsula in the 3rd century BC. After they had subjugated the peninsula, Cadiz and its environs became an important naval base in the empire; peace and prosperity reigned as the Iberian tribes became increasingly pacified and Romanized. However, Spain was ripe for an invasion after the Western Roman Empire disintegrated in AD 476.

A succession of bellicose tribes from Northern Europe, including the Vandals and Visigoths, attempted to conquer Andalucia. Yet they were easily defeated by the Moors in 711, after Tariq ibn Ziyad, the Muslim ruler of Tangier, landed in Gibraltar with a force of 10,000 men. The Visigoth army was decimated, and within a few years, the Muslims had taken over all of the Iberian Peninsula except for small areas in the north.

In the 8th century, the Moors named a small settlement north of Cadiz ‘Scheris,’ from which Jerez and Sherry derived. Unfortunately, many vineyards disappeared from the landscape during the Muslim occupation, and the region faded into obscurity until 1262 AD when it was liberated by Alfonso X. By 1492, the last Moorish city of Granada was back in Christian hands. That same year, Christopher Columbus set sail from El Puerto de Santa Maria and discovered the Americas. Meanwhile, the (still) wines of Sherry became renowned in England during the 1500s, as mentioned in the plays of William Shakespeare. Barrels of wine were shipped from El Puerto de Santa Maria, and the town became a base for the Spanish royal galleys. Yet Andalucia had a love/hate relationship with its English customers; Sir Francis Drake attacked Cadiz’s harbor in 1587. Then, in 1596, Anglo-Dutch armies razed Cadiz to the ground.

However, a golden age dawned in the 18th century, when El Puerto flourished on American trade and earned the nickname ‘Ciudad de los Cien Palacios’ (City of the Hundred Palaces). Meanwhile, after Dutch merchants commercialized distillation, producers began to add grape spirit to their Sherry wines to prevent oxidation and spoilage during the long sea voyages to Northern Europe. From the 1830s onward, an influx of British money saw the development of Sherry’s iconic bodegas, including Gonzalez Byass and Harveys. Today, Jerez de la Frontera’s most legendary families are a mixture of Irish, British, and Spanish origin due to the intermarriage of wine traders over the past 150 years. Moreover, although the area under vine has declined significantly since the 19th century, Sherry has not given up the ghost. The industry has recently generated greater prosperity by investing in new styles and engaging with key influencers on social media.

For over 2000 years, the hills between Jerez, El Puerto, and Sanlúcar have been the heart of Andalucia’s wine industry. Yet vines are grown outside this historical boundary today: producers in the communes of Lebrija, Chipiona, and Chiclana are entitled to market a DO Sherry wine. Nine municipalities are in the Sherry business, cultivating grapes on calcareous white chalk known as albariza. The key variety, Palomino, only yields suitable wine on this limey clay terroir that reaches an apogee in the pagos (districts) of Carrascal, Macharnudo, Anina, and Balbaina. Meanwhile, sandy coastal vineyards in the eastern section are more suited to Moscatel.

Climatically, the Sherry Triangle is a quintessential Mediterranean vineyard: warm and dry, with little rainfall between May and September. Some of the hottest conditions are encountered in Montilla-Moriles, just south of Cordoba. Both chalk and sandy terroir are found here, although the principal grape variety is not Palomino. Instead, unctuous sweet wines are made from the Pedro Ximenez grape: rich and decadently potent—Heaven for sugar fanatics – hell for dentists.

Sherry’s greatest virtue is finesse. The best Finos and Olorosos, born of the white chalk and climate, are spellbinding expressions of wine and wood. Yet terroir is ultimately a secondary consideration in Jerez de la Frontera; Sherry is handcrafted, first and foremost, in the cellar.

The vast majority of dry Sherries are made from 100% Palomino. Grapes are harvested fairly early in the fall, usually the first week of September. The fruit is then pressed quickly at vinification facilities on the outskirts of Jerez or in the vineyards themselves. Historically, fermentation was undertaken in wood or concrete vats. However, most bodegas now vinify their wines in stainless steel; precisely controlling the fermentation temperature greatly benefits fruit expression. After the process has finished, the wines will be classified into three broad categories: Finos, Olorosos, and Rayas (inferior lots). Wines deemed the cleanest and most aromatic are destined to be Finos (or Manzanillas, if they are to mature in a cellar in Sanlúcar). Chunkier, fuller-bodied wines will be the Olorosos.

Wines classified as Finos are then fortified with a wine-based distillate to about 15.5 percent alcohol by volume and added to 600-liter casks already containing wine from a previous year. Then the ‘Solera y Criaderas’ process can begin – maturation in wood barrels is the single most important stage in the production of Sherry. But, unlike red Bordeaux, wines from different years are blended and aged together before they are bottled. The Solera system is the unique process by which Sherry is produced.

You can discover more about this system here in our – Comprehensive Guide to Sherry

Except for the very oldest and rarest of cask-select bottlings, there is a worrying supply and demand imbalance in the Sherry market. To be blunt, many consumers still regard it as tragically passé. Moreover, the piquant flavors of Sherry are not for everyone: Finos (and the Manzanillas that hail from Sanlúcar) can come across as being razor-sharp, with a salty edge to boot.

To the uninitiated, Amontillado and Oloroso Sherries can taste salty, slightly bitter, and introverted; the cream and other sweet Sherries can be cloying to advocates of dry whites. But with an open mind and a curious palate, you will find that these are wines of nuance, subtlety, and tremendous value. The industry is working hard to deliver this message that Sherry isn’t just a sweet sipper for old English ladies. Instead, it is a multifaceted, intricate wine with enough versatility to be served before, during, or after a meal.

So why the apathy from some quarters? Part of the problem is complexity. Sherry is not easy to understand: there is a huge myriad of styles and categories available. An update to the DO rules in 2021 has not simplified matters, albeit many producers and critics favor the new framework. Today, bodegas in any part of the Sherry region can mature wines for sale; historically, only wineries in Jerez, Sanlúcar, and El Puerto had that privilege. New grape varieties – Vejeriego, Perruno, and Beba – were authorized by the Consejo Reguladro, and two new categories were unveiled: Manzanilla Pasada and Fino Antiguo.

But, most dramatic of all, Sherry can now be produced as a table wine – fortification is no longer obligatory. Because of global warming, bodegas can now market Fino and Manzanilla styles that reach the minimum of 15 degrees without adding grape spirit. In the increasingly sweltering climate of southwestern Andalucia, this is entirely possible. Nevertheless, Solera’s aging regulations (minimum of two years) remain unchanged.

The true magic of Sherry, however, remains its diversity. But what makes one winemaker’s Amontillado different from that of another? Unlike the differences among Napa Cabernets or Grand Cru Burgundies, it’s not about the quality of the fruit or the toast of the oak, for everyone uses Palomino and inert barrels to make Sherry. It boils down to mesoclimates within the three Sherry towns or even microclimates in different parts of the same bodega, which is why the solera row is always positioned closest to the ground; blending and aging also play a major role. Jerez is the furthest inland of the three towns, and consequently, it is hotter than El Puerto or Sanlúcar, with summer temperatures regularly rising above 100°F. As a result, wines from Jerez, especially the delicate Finos, are fuller and nuttier than wines aged closer to the ocean.

In Sanlúcar, the humidity carried on the wings of strong marine breezes fosters vigorous growth of a distinct flor, and the resultant wines are paler, finer and taste more of green apples than those matured elsewhere. “Here in Sanlúcar, the flor is very active; it doesn’t die like it can in Jerez,” says Bertrand Nouël, export director for Barbadillo. And it’s about 10°F cooler on an average summer day in Sanlúcar than in Jerez.

Beyond that, it is predominantly a question of blending, when the cellar master chooses to move wines from criadera to criadera, and how much they transfer at a time and aging. Older Sherries certainly have more character than younger ones, and the percentages of older stocks versus younger wines will determine a house style or the character of a reserve bottling. From a collector’s or connoisseur’s perspective, the older wines are the most intriguing, complex, and idiosyncratic. An older Oloroso, Amontillado, or Palo Cortado can be packed with years’ worth of individuality, to say nothing about the smooth, nutty palate and sublime lingering finish. As you would imagine, such Sherries are many times more expensive than the basic bottlings. For everyone else, a simple chilled Fino or Manzanilla with appetizers instead of yet another glass of white wine could be a vinous epiphany. Why not give Sherry a try?

Palomino: The quintessential grape for Sherry in Andalucia, Spain's southern delight. Unearth tradition's essence in every sip.

Find out moreThe Moscatel grape, renowned for its aromatic allure and luscious sweetness, also plays a significant role in the world of Sherry. This versatile grape variety contributes to the creation of exceptional Sherries, adding depth, complexity, and a touch of honeyed richness to these fortified wines.

Indulge in the Sweetness of Pedro Ximénez: A Resplendent Grape for Andalusia's Montilla-Moriles. Experience the Richness of Sweet Sherries & Fortified Wines.

Find out more

The Moors had a lasting impact on Andalucian cuisine: citrus, saffron, rice, and olives were absent from Spanish kitchens until the 8th century. The tradition of barbecuing meats and using sauces flavored with cumin and saffron can also be attributed to the Arab and Berber conquerors. Today, tomatoes and peppers are key ingredients in local cooking – Sanlúcar de Barrameda is famous for its grilled Atlantic fish, especially sardines, and deep-fried squid. Meanwhile, the tapas bars of Jerez are an essential part of any Andalucian itinerary. In southern Spain’s restaurants and tapas bars, patrons ask for it more by name than by brand: Un Fino, Una Manzanilla, etc. More often than not, Sherry is the first drink of the day, and generally, it’s a Fino or Amontillado, depending on what the thermometer says.

However, Sherry isn’t only an apéritif wine; it can complement everything from the salty to the sumptuous to the sublime. A dish of nuts or olives is brought to another level by a well-chilled, bone-dry Fino. Shrimp and raw oysters sing with Manzanilla. Any game bird and other types of white meats are natural matches for a more complex Amontillado. And, believe it or not, a plate of beef smothered in a velvety sauce will only taste better washed down by a dry Oloroso (and even better if some of that Oloroso was used in the sauce). And then there’s cheese or dessert.

Here are our guidelines for serving Sherry with food. Because Spanish dishes are fun to prepare and even better to eat, staging your own tapas party is a highly recommended Saturday evening activity. Ensure your Fino or Manzanilla is fresh and cold, and your servings and drink-pours are on the small side.

Andalusian Gastronomy Guide: Read more

Immerse yourself in Jerez de la Frontera's vibrant flavors and uncover hidden culinary gems with our expert insider guides. Plan an unforgettable trip today!

Read more

Immerse yourself in Córdoba's vibrant flavors and uncover hidden culinary gems with our expert insider guides. Plan an unforgettable trip today!

Read more

Immerse yourself in Granada's vibrant flavors and uncover hidden culinary gems with our expert insider guides. Plan an unforgettable trip today!

Read more

Immerse yourself in Ronda's vibrant flavors and uncover hidden culinary gems with our expert insider guides. Plan an unforgettable trip today!

Read more

Immerse yourself in Seville's vibrant flavors and uncover hidden culinary gems with our expert insider guides. Plan an unforgettable trip today!

Read moreIf you would like us to customize an exclusive luxury tour, contact us and let us know your travel plans. We offer luxury food and wine tours for private groups of a minimum two guests. In addition, all of our private, chauffeured tours are available year-round upon request.